Nearing the end of our Pride Month Extravaganza, I want to shift the conversation to discuss a book that isn’t speculative fiction. In fact, it isn’t fiction at all. However, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t matter to readers and writers of queer SF; far from it.

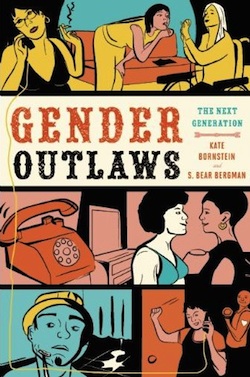

I say this because one significant section of any writer’s proverbial toolbox is their resources—loosely put, the things they pull from to craft stories. Those resources include a writer’s own life experience, in the “write what you know” sense, but they also definitively include other folks’ experiences, discovered via research. Nonfiction plays a vital role in the creation of fiction; a singular resource for any writer, especially a writer of speculative fiction, is the wide world of nonfiction. In some cases, those resources are physics textbooks—but in others, when speculating on gender and sexuality, they can be books like Kate Bornstein and S. Bear Bergman’s anthology, Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation, published by Seal Press in 2010.

I also say this because—even if you aren’t a writer yourself, just a fan of queer speculation—the ethos of extrapolation and a real sense of wonder are both on unabashed display in the essays contained in Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation. There’s something that I would call speculative sensibility here: the desire to push boundaries, make changes, and claim new, far-out spaces.

“Gender Outlaws collects and contextualizes the work of this generation’s trans and genderqueer forward thinkers,” says the flap copy. It’s the most expansive, provocative, wide-ranging collection of essays on genderqueer and trans* identities I’ve encountered. Bornstein and Bergman have included a diverse range of voices, all discussing gender, identity, and experience from their own unique viewpoints. Frankly—it’s a brilliant, moving book, both an ideal introduction to ideas of pushing/fucking/transcending the gender binary and a celebration of claiming identities outside, inside, and across the spectrum of that deconstructed binary.

These issues are of obvious interest to me, as a genderqueer/woman writer and editor—but the writings of the folks in this book have also opened my eyes further, past my own experience and into the experience of others. There are essays on the issue of choosing white names during transition for trans* people of color, and the echoes of colonization that this implies—Kenji Tokawa’s “Why You Don’t Have to Choose a White Boy Name To Be a Man in This World”—to j wallace’s “The Manly Art of Pregnancy,” on how having a body that can carry a child to term is just one way to become a father. For that matter, there are humorous pieces—”the secret life of my weiner” by cory schmanke parrish, and all of the pieces written in conversation by the editors—that nonetheless speak to intense issues of personal development and the creation of new, fresh understandings of gender.

The development of a new language of self and of authentic ways to discuss being trans* is a gorgeous display of genius, bravery, and extrapolation. Reading this book in the context of writing about it for our Pride Month Extravaganza—as a valuable, vital resource for folks who are interested in expanding their worlds, whether through reading science fiction or writing it—calls to mind Joanna Russ’s essay, “The Image of Women in Science Ficton,” in which she discussed SF’s failure to engage in “social speculation” as well as speculation in the hard sciences. She accused the field in the 1970s of a refusal to examine received cultural ideas about gender, a blind acceptance of stereotypes and social dogma. While she was discussing feminism and the role of women at the time, that very sentiment is equally applicable to contemporary representations of gender in speculative fiction—the necessity of pushing past received cultural ideas about the binary, of being willing to engage in social and cultural speculation.

These international, intersectional, prismatic, radical “gender outlaws” are “writing a drastically new world into being.” What are we doing in speculative fiction, at its most illuminative, but writing new worlds into reality? And why wouldn’t those new worlds contain gender outlaws—trans* folks, genderqueers, people fucking up the binary and experimenting with bodies, embodiment, ways of existing and ways of making the self whole?

I don’t know what beauty is, if it isn’t this:

Gwendolyn Ann Smith’s “We’re All Someone’s Freak,” about resisting the urge to police self-definition within the borders of our own community.

Raquel (Lucas) Platero Méndez’s “A Slacker and Delinquent in Basketball Shoes,” about the brief history discovered in old paperwork of Maria Helena N. G., a person arrested for being assigned female but living as male in Spain in 1968, during the Francoist years. (I will admit, this piece made me tear up—the sense of history and solidarity over the years, and such recent memory, is both painful and comforting.)

“I am the ‘I'” by Sean Saifa Wall, an exploration of intersex identity that ends imploring, saying, “Those of us with intersex conditions and varying gender identities are the only ones who can know and tell our own stories.” (111)

Francisco Fernández’s “Transliteration,” a piece in both Spanish and English by an Argentinean writer about the spaces between and across languages that offer him a way to claim identity in the transition from “girl to boy,” and from boy to manhood.

And, breathtaking for me each time I have read it, “transcension,” a comic by Katie Diamond and Johnny Blazes that explores being a genderqueer person flickering back and forth across different embodiments, pronouns, and ways of being with a female-assigned body. They also discuss fears of using the words “trans,” feeling undeserving of it, in ways that speak to me so vibrantly it is actually somewhat painful. I don’t think that any of the essays in this book is The Best, because they all form a tapestry that would simply not be the same if a single voice was lost, but this is the one that speaks to me—the one that gives words. (And, well, that’s a very personal thing to put out in a piece of criticism, too. But here I am.)

This is a book that makes realities out of words, claims spaces—takes up space—that folks who are trans* and genderqueer must claim to survive, to love ourselves. It’s also a book that anyone can read and be astounded by, be challenged by, be whacked over the head with the clue-pillow by, be brought to tears by—you name it. This is a book that writers of speculative fiction can use to inform their writing of the “other,” of folks with experiences different than their own, and to do it with respect and the grounding in research that—sometimes, hopefully—prevents epic fuck-ups.

Read it for the fifth and final section of the book, “And still we rise,” where the essays explore the challenges and dangers of trans* life with honesty, with terror, with rage, and with courage. Roz Kaveney’s “Shot, Stabbed, Choked, Strangled, Broken: a ritual for November 20th” (the trans* day of remembrance) is a staggering poem. The truth—and the horror of that truth—contained in sharp, short, evocative lines in this poem will stay with the reader for hours, days, afterwards. Read it for the final essay, “Cisgender Privilege: On the Privileges of Performing Normative Gender,” and think through the survey of questions to determine levels and areas of privilege in gender performance. Many of these I do not suffer, though friends and loved ones do—but there are others, oh, yeah. (“26. On most days, can you expect to interact with someone of a gender similar to your own?”—Huh, no, actually. No, I can’t.) That closing survey, in particular, is useful to the person who wants to know more—whether they themselves are queer, or trans*, or outside of the normative social contract, or not. It’s revelatory, certainly.

So—like I said, Gender Outlaws: The Next Generation may not initially seem to fit in with a series on queering speculative fiction at first glance. It does, though—because this is a space where we discuss writing new worlds into being. Gender Outlaws is speculative, extrapolative, filled to bursting with a sense of wonder—and, in the context of reading it not only as a genderqueer person (though that was an uplifting and emotional experience I cannot even communicate to you fully, in this space) but as a science fiction critic, I can also call it an invaluable resource for the readers and writers who want social speculation.

Accept this stuff—this is happening right now. This is the razor’s edge of identity, of gender, of pushing the binary until it becomes something entirely other. These are real people, telling you their real stories, letting you in. They are offering of themselves for others who need these essays, these stories, these voices speaking into silence. These stories are often intimate, painful, personal; these stories ring with the truth of experience. Read them, respect them, delight in them—and let them write new worlds into being on your mind and heart, as well.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.